Cayman Islands expand protected areas

3 minute read

These days we often use the word ‘resilience’ to describe the capacity of wildlife and habitats to bounce back from the stresses and threats they face. But in the Cayman Islands, our friends on the front line of marine conservation have shown that they are resilient too.

The Cayman Islands Department of Environment (CIDoE), with help from the UK government’s Darwin Initiative, first started talking with local communities about expanding its existing Marine Protected Area (MPA) network over a decade ago. And despite various threats to their ambition (including a global pandemic), as well changes of government, the new enhanced MPA network they championed has finally come into force this month! Now about 48% of their shelf waters are designated as no-take zones – and this huge result is testament to the resilience of the CIDoE as well as Caymanian communities and other partners in getting this inspirational work over the line.

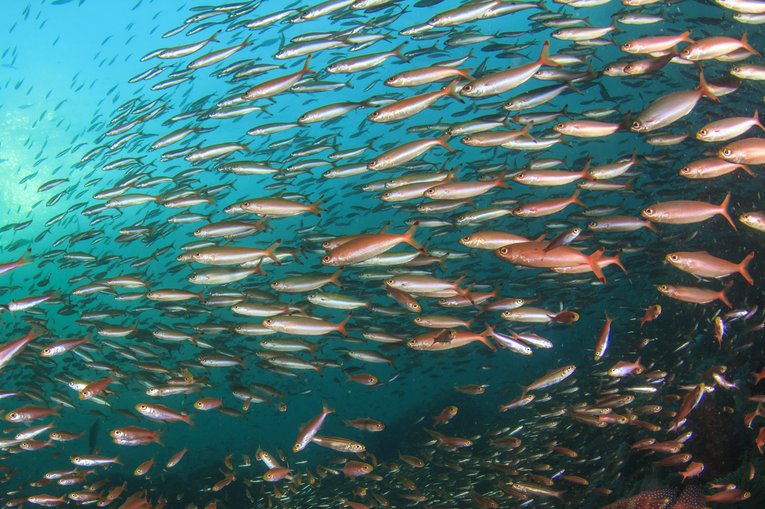

Credit: Rich Carey via Shutterstock

Director of CIDoE, Gina Ebanks-Petrie stated: “Since Marine Parks were first introduced in the Cayman Islands in 1986 they have remained at the heart of local marine resource management initiatives. We are extremely proud that the Cayman Islands are once again setting the example in the Caribbean with the introduction of these bold new marine protection measures.”

The Cayman Islands is one of five UK Overseas Territories in the Caribbean, about 200 miles northwest of Jamaica and 150 miles south of Cuba. Its three islands – Grand Cayman, Cayman Brac and Little Cayman – have an area of 102 square miles and support a population of 66,000 or so, with a strong financial and tourism sector supporting the national economy. The first MPAs were designated in the Islands some 35 years ago, originally designed to protect fragile coral reefs, mangroves and seagrass beds. While these MPAs were contributing to the protection of vulnerable marine species and habitats, CIDoE’s research showed gradual declines in marine biodiversity over time. This was primarily due to considerable population growth and a range of new threats not originally contemplated during the design of the original MPAs.

To try to halt, and where possible, reverse these declines, MPA expansion plans increased fully protected areas by nearly 250% across the Caymanian coastal shelf. Prior to the expanded MPA system coming into force, 14% of Cayman’s coastal waters were under full ‘no-take’ protection. However, with MPAs having undergone expansion, today we see nearly half of Cayman’s coastal waters as no-take zones. This increases the resilience of Cayman’s waters in dealing with local threats such as recreational/artisanal fishing and coastal development, while national population increases and economic growth continue to apply pressure. With Cayman also possessing the largest contiguous mangrove forest in the whole of the insular Caribbean region along with acres of seagrass beds, protection of these ‘blue carbon’ habitats will also support the global fight in tackling the climate crisis.

Credit: Peter Richardson

Given the track record of the CIDoE, we can trust that they will achieve their ambitions and properly manage and protect these sites - the remarkable turn-around of Cayman’s Nassau grouper fish populations is a perfect example. This critically endangered species underwent a severe local reduction, mostly due to over-fishing. However, 15 years of collaborative Nassau grouper management interventions, including MPAs, resulted in the population on one of its islands, Little Cayman, increasing fivefold in size from approx. 1,500 fish in 2005 to > 8,000 in 2020. Additionally, the Nassau Grouper population on the island of Cayman Brac increased from approximately 500 fish in 2005 to > 4,000 fish in 2020, an eightfold increase in that island’s Nassau grouper population. Likewise, CIDoE conservation efforts have seen their nesting sea turtle populations increase over the last 20 years.

Cayman’s marine wildlife is in safe hands, and now that huge areas of habitat are fully protected, the future looks a lot better for Cayman’s marine ecosystems and the people that depend on them.